Nutley Lodge Master Franklin Suco presents a gift to W. Ben Hoff in thanks for the lecture delivered there Monday night. Hoff is Master of New Jersey Lodge of Masonic Research and Education in Trenton.

The yearlong Masonic education program at Nutley Lodge No. 25 continued in fine style Monday night with the appearance of W. Ben Hoff. The Worshipful Master of New Jersey Lodge of Masonic Research and Education in Trenton journeyed north to share with the brethren one of his always illuminating presentations. This one concerned the history and diversity of ritual ciphers.

Ben is an avid researcher of Craft Masonry rituals – their history, variations and, when possible, their appearance in cipher books, official or otherwise. His personal library of ritual books includes genuine antique treasures like “The Master Key” by John Browne from 1794 (a book that even Mackey said was rare, and that was 150 years ago), and the more famous Antient ritual exposures from the 1760s, like “Three Distinct Knocks.” Of more modern publications, Ben has a library of American and English ritual books, some published officially, others not.

When giving these talks, Ben always brings a batch of these texts for the brethren to see and handle. Monday night we had the chance to peruse a variety of books, including a handwritten ritual book, in code, from Aurora Lodge No. 3 in New Hampshire (which no longer exists). I think it was a 19th century vintage. Its code was the “dreaded single-initial” abbreviation style, as opposed to the unique symbol characters in the ciphers of New Jersey and elsewhere. And he also distributed brief excerpts from New Hampshire’s official ritual book of 1948. In both samples, it was hard to decipher everything because that jurisdiction’s language differs very slightly. But other variations are major, like the absence of Deacons taking up the Word during the opening.

The proliferation of ritual exposures was natural, Ben explained. Although published commercially and without official sanction of the Grand Lodges, these books were mightily sought by the brethren for use as memory aids. Even those books published by anti-Masons for the purpose of diminishing the fraternity’s mystique and allure were snatched up by Masons struggling to study independently. “We’re not supposed to write (the secrets of the degrees),” he added, “but nobody ever said anything about buying.”

One might be tempted to think the study of Masonic ritual ciphers would be dull and dry. The truth is the real story of Freemasonry is encoded in those pages. The comparison of one modern ritual to its ancestors reveals more about the Craft than any dozen lame “Templar Chapel Decoded!” type books on the point-of-sale rack in Barnes & Noble. But it requires patience, and it is necessary to read history for context. From there you can see with your own eyes how the lodge of the tavern became the lodge of the temple; how lectures were taken away from the brethren assembled and assigned to a lone orator; how Openings were changed from the EA° to the MM°; and how beautiful prose was excised by ritual committees that had no idea of the meaning and purpose of those words.

There were changes arising outside the temple as well.

William Morgan’s ritual exposé resulted in the scandal that almost destroyed the fraternity in the early 1800s. To cope and attempt a comeback, many of the Grand Lodges sent delegates to the Baltimore Convention in 1843, where the feasibility of a nationwide standardized ritual was seriously proposed. The anti-Masonic movement of the era produced America’s first political third party: the Anti-Masonic Party, which enjoyed significant electoral success, even electing a governor in Vermont.

During the Civil War, the prolific author Rob Morris devised his Mnemonics system, which he offered as a potential standard ritual for the country’s recovering Masonic fraternity. That ritual is seen today in the work of Connecticut’s lodges, among others.

The advent of ritual books caused the fraternity to obsess over its ceremonies. By having the printed word for reference, Masons became devoted to letter-perfect performance of the degrees. Ceremonial form became more important than instructive substance, and passing generations of mistaken Masons came to believe there never have been changes to their rituals. Sound familiar?

“The essence of ritual is not the precision of the words,” said Hoff, whose research will result in a book on the evolution of Craft ritual, the chapters of which he presents as papers to our research lodge. “Originally there was no standardized ritual. To this day in England there is no standardized ritual!”

“The essence of ritual is not the precision of the words,” said Hoff, whose research will result in a book on the evolution of Craft ritual, the chapters of which he presents as papers to our research lodge. “Originally there was no standardized ritual. To this day in England there is no standardized ritual!”The point, he added, is that these ceremonies need consist only of their necessary initiatory elements (the entrance, circumambulation, etc.). This does not mean anything goes in the degrees, but rather lodges do not have to be the cookie-cutter clones we have today. “Lodges with non-standardized rituals have brethren who are more passionate about preserving their lodges’ rituals and heritage.” They have to be more careful; they don’t have books to pass around. “They also spend more time visiting other lodges to see what they do differently. It’s cool!”

As regards New Jersey’s ritual, what we see today printed in plain English in our books once was merely commentary on the actual ritual, which we know in code. This added commentary gradually became incorporated into the ritual itself, making the ritual more complicated... resulting in the demand for written texts.

New Jersey ritual ciphers date back more than a century, to “King Solomon and His Followers: A Valuable Aid to the Memory.” The MM° Opening in this unauthorized book shows the Deacons being summoned to the West; charged by the SW to satisfy themselves that all present are MMs; and then traveling East by the North and South. No Word is taken up. Instead, a Deacon halted in front of an unfamiliar brother, until he was properly avouched.

Another unofficial New Jersey cipher, titled “Ecce Orienti” circa 1918, begins with a 13-page discussion of the Essenes, a term used to confound the uninitiated (and incidentally a term used about 30 years before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls).

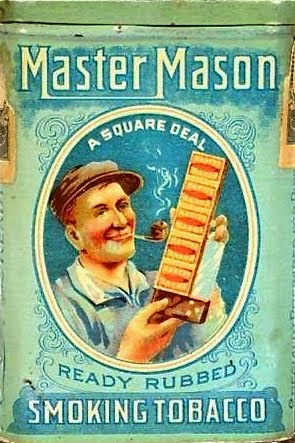

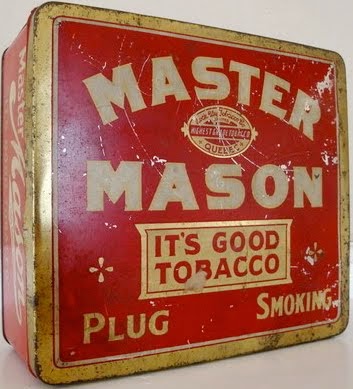

The publishers of both of these books also printed versions for other Masonic jurisdictions. Remember this was the golden age of fraternalism, when publishers, manufacturers and vendors of all kinds could earn their livelihoods by gratifying the needs of the hundreds of thousands of men who comprised the countless fraternities, benefit societies, and other groups upon which people depended for their social lives and economic security. The codes employed in these pages are recognizable to Masons today.

The same is not true of the aforementioned Browne’s “The Master Key.” That author devised a cipher that replaced vowels with the letters of his last name.

A = B

E = R

I = O

O = W

U = N

Y = E

So, of course, the use of a B could indicate an intended A... or it could just be the B.

The Magpie reader who can decipher the following phrase will receive a pint of Guinness and a fine cigar next week at the Alex Mark Hilton.

1 comment:

Your cipher usage of Browne is not completely correct.

The phrase you give is obviously "The king and the kraft with" ...

however, as noted by Mackey, initial capitals have no value, and supernumerary letter are often inserted. Additionally, in Browne's work, aeiouy then become kcolnu.

Post a Comment