|

| Standing before a bookcase stocked with a complete set of AQCs, author James Wasserman addressed a packed room May 29 at the Chancellor Robert R. Livingston Library at the Grand Lodge of New York. |

Author James Wasserman was the guest lecturer for “Freemasonry and the Quest for Liberty” at the Chancellor Robert R. Livingston Library at the Grand Lodge of New York May 29, promoting his latest book The Secrets of Masonic Washington: A Guidebook to Signs, Symbols, and Ceremonies at the Origin of America’s Capital.

I think library Director Tom Savini should be proud. It was an excellent event that drew a standing room only crowd, which is amazing considering how many other things there are to do in New York City on a warm, still, summertime Friday evening. The Master of The American Lodge of Research was there, as was the Junior Warden of Civil War Lodge of Research, and other accomplished people in the field of Masonic education, like John Mauk Hilliard. But it seemed as though most of those present were not Masons, which indicates to me that Freemasonry can pique the interest of educated adults by hosting cultural events in elegant settings.

“Freemasonry is the spiritual component of the greatest political experiment in history,” said Wasserman, introducing his thesis of the Craft’s significance in the birth of the American Republic. He divided Freemasonry’s inevitability into three historical epochs. The first is Biblical history, wherein we see man attempting to govern himself in Eden, followed by that gradual evolution of patriarchal leadership, from Noah to Moses. His point: that the political governance we know today has a spiritual basis. He illustrated this with a recollection of the prophet Samuel who sagely warned the Israelites that they should be careful what they wish for when it comes to hoping for a king to lead them. Investing their faith in a temporal king would displease the Lord. Quoting 1 Samuel 8:10-14:

And Samuel told all the words of the Lord unto the people that asked of him a king.... This will be the manner of the king that shall reign over you: He will take your sons, and appoint them for himself, for his chariots, and to be his horsemen; and some shall run before his chariots.... And he will take your daughters to be confectionaries, and to be cooks, and to be bakers. And he will take your fields, and your vineyards.... and give them to his servants.

A period of about 500 years in which the Hebrews would be ruled by kings ensued, ending with the Babylonian Captivity. This, Wasserman said, would not have escaped the notice of those who wrote and signed the Declaration of Independence, with its list of grievances against George III.

We remember the somber observation of the Declaration’s first paragraph, where it is stated that people with sufficient cause have the right to dissolve political ties with others for their self-preservation. Then of course there is the immortal, stirring, poetic clarion of the second paragraph.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

What many of us probably forget is the list of several dozen very specific complaints enumerated against the Crown, “a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny,” and that foreshadow the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

At approximately the same time Samuel’s warning came to fruition, Classical Greece and Rome were giving the world new forms of government, Wasserman explained. Direct democracy was practiced by the former (c. 500 BCE to 322 BCE), and an embryonic form of representational government was established by the latter (c. 509 BCE to the first Caesar). Greek Democracy proved to be unwieldy and inevitably dysfunctional; Roman politics morphed into militarism, which led to empire and “bread and circuses” until “leaner, meaner and hungrier barbarian tribes” undid it, he added. A millennium later, the Catholic Church proved to be the stabilizing force that established a political hegemony over Europe’s many regional rulers. This brings us to Wasserman’s second, if ironic, historical period of Freemasonry’s eventuality: feudalism.

While this term often is applied to other places and times, feudalism is the political and legal system of medieval Europe in which peasants, who were bound to the land on which they lived, were in effect possessions of the lords who owned those lands. Needless to say, these peasants, or “serfs,” had no political rights or access to justice. Even the advent of the Magna Carta in 1215, a revolution well remembered by the Founding Fathers, did not adequately address the rights of the peasantry. This backdrop reveals the glaring contrast embodied by the operative stone masons who were free to travel to practice their craft.

From the 12th to the 16th centuries, thousands of cathedrals, churches and other stone structures were built across the British Isles and throughout Europe, Wasserman explained, “about 1,200 of them, in 25 countries, remain today.” Their existence is thanks to “skilled craftsmen, geometricians and architects” who were permitted and capable of electing their own officials, occupying their own residential areas, tending to their own charitable and health care benefits for their workers and dependents.

Masons developed the guild system, which expanded on those existing freedoms, adding the ability to establish rates of pay, delineation of responsibilities, prevention of fraud and, of course, systems of recognition – those ritualized answers to questions that affirm ownership of one’s mind.

“Secrecy is the right of a free person,” Wasserman said, thus operative masonry is the second building-block, set atop the foundation stone of Biblical man’s struggle to establish self-rule, leading toward a culmination of individual liberty and political governance. That operative masonry, with its “magnificent edifices reaching skyward,” best represents the singular experience of a free person, for its successful transformation of mysteries, like geometry, into permanent achievements.

Of course before that zenith is reached, Europe evolves through the Renaissance, described by Wasserman as the offspring of the communion of Christianity and Islam, and the Reformation, and it is shortly thereafter that masonry undergoes an important, if enigmatic, transformation. The 17th century saw membership in masons’ lodges opened to men who had no connection to the building trades. The best known of these is Elias Ashmole (1617-92), an intellectual possessing a strong interest in Natural Philosophy, who was drawn to the society for its possession of Sacred Geometry and other hidden wisdom.

Wasserman’s third building-block, his capstone, is the Enlightenment. The labors of Isaac Newton, Benjamin Franklin, Denis Diderot, Christopher Wren and so many others gave rise to and defined the Enlightenment, when “rationality, as a means to understand reality, rejected the hopelessness of earlier Catholic thought.” To Wasserman, the United States, its Declaration of Independence, its Constitution and Bill of Rights embody mankind’s desire for spirituality. “The human soul craves religion, spirituality, and oneness with God,” he said, whereas atheism and agnosticism “leave an unsatisfied hunger in the human psyche.” And Freemasonry is a companion to this new nation and its government. It offers to the seeker after knowledge that very quest, without causing him to leave his intellect at the door of a church. “I believe that resulted in the greatest quest for human liberty in history. The United States of America and its entire legal and ethical system is based on the Bible, and it is no mistake to identify America as a Christian country. (I’m Jewish, by the way.)”

For James Wasserman, Freemasonry is the “most refined advance of Western culture.” While it consisted of wealthy elites at the time it took root in America, it grew and spread throughout the new nation when it embraced soldiers, artisans, merchants and other self-made men, proving itself to be an ordered society of far-thinking individuals who also would work outside of the lodge to help society strengthen its democracy by dismantling social and economic barriers.

It was a great event for the Livingston Library. The only problem is the talk Wasserman gave was more interesting than the book he wrote. In recent years there have been a bunch of quality books about Freemasonry that are excellent resources for Mason and non-Mason alike, and Wasserman’s “Secrets” definitely ranks among them. His book is one of the more lavishly illustrated, with dozens of outstanding color photographs – many of them close-ups – revealing the amazing details of the symbols and codes embedded in the architecture of our nation’s capital.

It was a great event for the Livingston Library. The only problem is the talk Wasserman gave was more interesting than the book he wrote. In recent years there have been a bunch of quality books about Freemasonry that are excellent resources for Mason and non-Mason alike, and Wasserman’s “Secrets” definitely ranks among them. His book is one of the more lavishly illustrated, with dozens of outstanding color photographs – many of them close-ups – revealing the amazing details of the symbols and codes embedded in the architecture of our nation’s capital.Monuments, statues, friezes, plaques, and other architectural voices tell the story of a peculiar system of human governance, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols that are mysterious to all but the initiated eye. But to be honest, a great many of these do not have connections to Freemasonry. To be sure, there are many Masons depicted in stone and metal, from George Washington to Albert Pike, and there are symbols that also appear in Masonic instruction, but the majority of these landmarks have oblique relationships to the Craft: Biblical figures, Greco-Roman gods, zodiac symbols, et al. “The Secrets of Masonic Washington” is valuable reading to the student of symbolism, but its Masonic education value is more contextual; in a way, it actually demonstrates that Washington, DC is not the physical manifestation of Masonic idiom that inexperienced or naïve Masonic students want to believe it is.

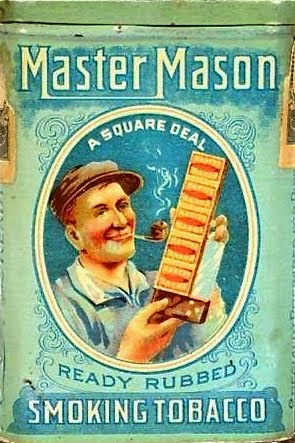

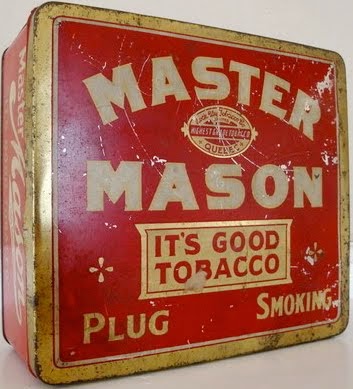

The stronger expressions of the Wasserman thesis are found in his discussion of the city’s man-made topography itself, and while nearly all Masons in the United States know at least a little about how Brothers L’Enfant and Washington sketched the earliest drafts of the federal city’s layout, Wasserman does a great service by poetically likening the square shape of the capital to both moral integrity, as in a square deal, and to a more esoteric understanding of the four physical elements of Fire, Air, Earth and Water. Other eye-openers include Wasserman’s perspectives on the Constitution’s relationship to the placement of the seats of the three branches of government; on the cruciform nature of the city’s design; and the spiritual harmony it all was meant to convey to the people. Invaluable reading, but outweighed by the Walking Tour that begins on page 71 that illustrates the many beautiful, but not necessarily Masonic, sights to see.

James Wasserman is not a Freemason. He said he is pursuing membership in the Craft in Florida, where he resides. It is no secret that many of the best books written about Freemasonry in the past 20 years were authored by non-Masons, and Wasserman deserves to be listed among those despite what I think might be a misguided enthusiasm to credit the Craft with too much.

1 comment:

Thank you for this article, as it makes one feel as if they were there for the lecture. Excellent.

Post a Comment